Is your Olympus Trip 35 really dead? What does the red flag mean? Many misconceptions about the Trip 35 are floating around – this article clears them up!

Olympus Trip 35 – Ghost in the Machine

- The Electric Eye – Selenium

- The Electric Cataract – Selenium degradation

- A working Trip is never manual

- The literal Red Flag

- Meaningless ISO Dial -A dead Trip 35's 'manual' mode

- Dissection – How to tell if a Trip 35 light meter is functional?

- Ghost in the Machine

- Should I buy "broken" Trips?

- Further Reading

- Sources

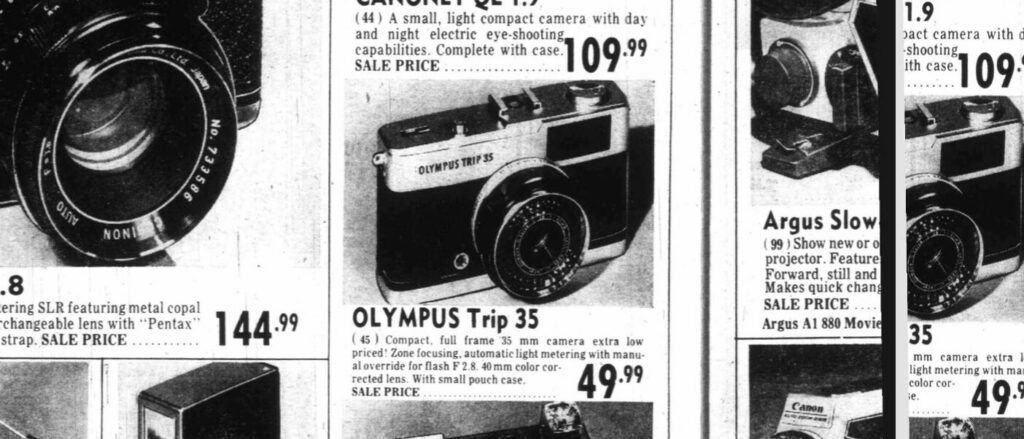

The Olympus Trip 35 is a cult camera – compact and well-built, it features automatic exposure, a simple four-zone focus system, and a great, sharp F2.8 Zuiko Lens. Introduced in 1967, it had a very long production run-up until the late eighties. More than 10 million units were sold, making it one of the most popular cameras from the time 1. However, this figure probably includes different camera models that were sold under the “Trip” brand.2

The original USP was ease of operation and extreme pocketability, promising fantastic daylight photos that literally anyone can use – thanks to the automatic exposure mode and the simple four-zone focusing.3

There is no question why this camera, marketed as a family camera, was a huge success. Today, fully working Trip 35’s are rarer and rarer to come by and are sold for quite high prices. A huge amount of offers are listed as either ‘defective’ or ‘untested ‘. However, there is a lot of conflicting and outright wrong information about this camera on the internet. Let’s tackle the most common misconceptions.

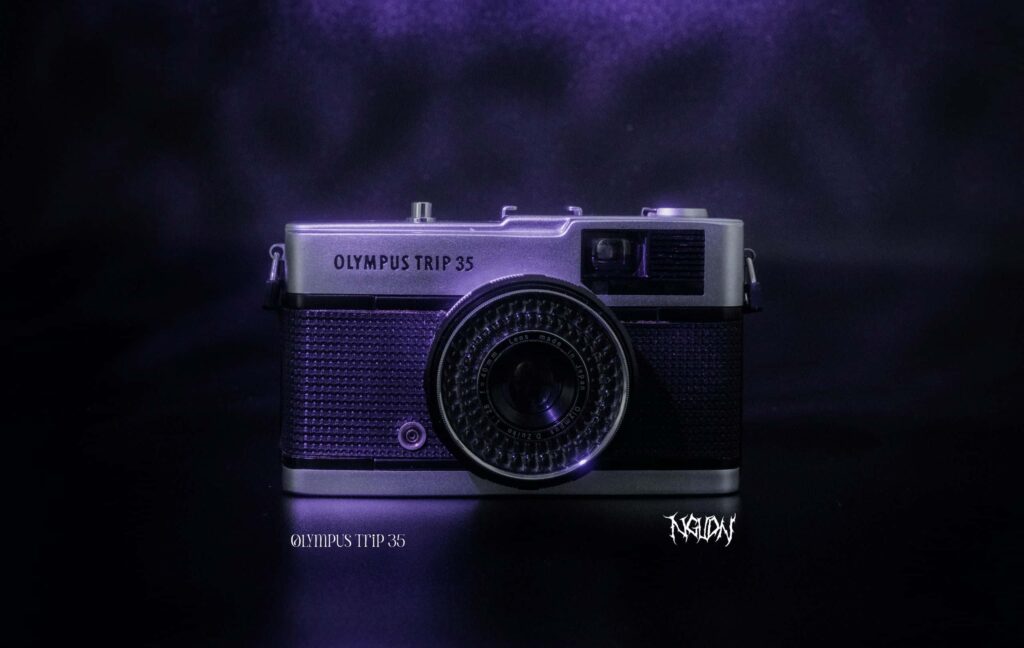

The Electric Eye – Selenium

The Olympus Trip 35 does not need an external battery, yet it offers automatic exposure. How does that work? It does so using something marketed as the ‘electric eye’.

The camera uses a built-in selenium light meter to determine the aperture required for correct exposure. ASA/ISO is set by the user through a dial at the front of the lens. The shutter speed in the automatic mode is chosen by the camera either at 1/200 or 1/40th of a second. There are no other shutter speeds available.

Selenium is a chemical element that – exposed to light – produces a tiny amount of electricity. This fascinating and useful effect was found in the late 19th century and was turned into a usable selenium light meter for photography in 1931.5

The camera uses a uniquely shaped selenium photocell at the front of the lens. There is a beautiful array of small lenses sitting on top of it, focusing the ambient light on the cell. While absolutely stunning to look at, nearly 60 years later this is the major breaking point of the otherwise sturdy camera.

The Electric Cataract – Selenium degradation

The photoelectric properties of selenium photocells can deteriorate over time, sped up by the environmental conditions which they are stored in:

High temperatures, high humidity, as well as high UV exposure damage the selenium cell and its sensitive layers. In the case of decade-old cameras, this is bad news – many of them are stored in hot attics, wet cellars, or stand in cabinets facing a window, being exposed to light for years and years. Many of them are without a lens cap and outside their original casings, making it easy for moisture and dirt to find their way into the delicate mechanics and electronics. The missing lens cap often speeds up the UV damage to the light meter and lubricated camera parts.

Tip: To prolong the life of your working Trip 35 it is mandatory to get a lens cap if the original one is missing. You can buy one online, 3D print it, or buy a third-party one that fits the lens. Store the camera in a dark, dry place at ambient temperatures between 15 and 25 degrees. Use silicate to reduce humidity. Storage in a humidity-controlled cabinet is optimal but expensive.

Unfortunately, a selenium cell cannot be easily restored or repaired and replacements are rare to find – especially if they are designed for a special purpose and in an uncommon shape like the Trip 35’s front-facing cylinder-cell. Finding a working replacement means finding a working Trip. You get the idea.

However, the selenium cell degrades, meaning it might still output a voltage too low to pass the internal resistor. If you are handy in repairs or electronics, you can swap out the resistor with a lower-rated one and technically still get the needle to move properly if you detect a voltage coming from the cell. I have never tried that method personally, since it requires disassembling the lens which can mess up the focus zones if done improperly. On top of that, I lack the required electrical skills.

If you are interested in how exactly this repair works, there is an incredible Repair Guide made by Peter Vis which explains the inner workings of this camera down to the smallest details. It is an exciting read and the best resource if you are attempting to revive your Olympus Trip 35 or learn about this camera in general. You can find it on his website.

A working Trip is never manual

The Trip’s user manual refers to a ‘manual’ mode. This ‘manual mode’ is engaged when the aperture ring on the lens is moved from (A) to one of the ‘fixed’ aperture values. This mode is locked at a shutter speed of 1/40th of a second 7

The correct and less confusing term for this mode would be “Flash Mode”, as it is designed for flash photography. This mode is the source of many misconceptions and false information.

The electric Eye never sleeps – the light meter is still engaged in flash mode

making it an “automatic” mode as well.

Contrary to many sources calling this mode manual, the light meter (if working) still engages in flash mode. The user only sets the minimum allowed aperture opening. The camera will still use the light meter to determine overexposure and stop the lens down accordingly. However, it will never open the aperture wider than the maximum allowed aperture, meaning you can still underexpose by setting the aperture value too high (closing the aperture too much).

If the camera is set at F5.6 and the camera determines it is three stops too bright, it will stop the lens down to around F16.

If however, it determines there is not enough light using F5.6 and F2.8 would be needed for correct exposure, it will stay at F5.6 and underexpose the image.

That means a working trip in flash mode operates like a camera in a very limited shutter-priority mode. You have one shutter speed to select (1/40th) and the camera will choose the aperture – in a range that you can specify by choosing the maximum opening (smallest f-number).

The ISO dial at the front of the lens is a mechanical part that covers or uncovers parts of the selenium cell, physically allowing less or more light to shine on it. On a working Trip 35, this can be used to influence the exposure as well. On a dead Trip, it has no effect whatsoever.

The literal Red Flag

When the working light meter determines underexposure in the automatic (A) mode, a red flag should rise in the viewfinder and the shutter cannot be pressed. If there is enough light, the camera takes a picture, determining the correct exposure and choosing the required aperture.

This is often the number one information people seek in online auctions: If the red flag behaves as described in the manual, the camera is probably working fine.

The red flag is not always a safe way to determine whether or not a Trip 35 is functional

– It’s behaviour is merely another indicator

However, several mechanical issues lead to a misbehaving red flag while the light meter is not dead. The red flag is made from plastic which can easily deform over time. A simple misalignment and the flag is blocked from entering the narrow slot that makes it show up in the viewfinder. In this case, the light meter is still functional but the camera seems broken.

A telltale sign of a dead meter is when the red flag always rises, no matter the (lack of) ambient light. This means the voltage produced by the selenium cell is not enough to pass the internal resistor as described above. This can mean that the cell is degraded (maybe even fully) or a cable is damaged.

This diagnosis either means: attempting a repair or declaring the camera as “dead”.

Meaningless ISO Dial -A dead Trip 35’s ‘manual’ mode

Having diagnosed a Trip 35’s meter as dead, it still has a final trick up its sleeve:

If the flash / manual mode is engaged on a Trip 35 with a dead photocell, the above-mentioned light meter will always determine no ambient light. As previously explained, the Trip’s light meter does not compensate for underexposure and won’t detect overexposure as the dead meter does not detect any light. Consequently, it will maintain the aperture at the value you’ve selected. Technically, you can still shoot the camera in flash mode at a fixed 1/40th of a second at the exact aperture you chose.

As the ISO setting is only changing the amount of light that falls on the selenium cell, it is irrelevant if the meter is non-functional. It will not allow you to manually influence the exposure. Only the ISO of the film will have an effect on exposure, meaning that the value is fixed as well at whatever film speed you put in the camera.

If your Trip 35s light meter is broken, the ISO dial is irrelevant.

Only your film speed will influence exposure.

I personally would refrain from calling this mode truly manual, as the shutter speed is fixed at 1/40th and the ISO is fixed by film selection. This is a very unintuitive way of exposing and is limited to a few scenarios. Very bright days, fast-moving action or more sensitive will be hard to expose properly.

There are modification guides on the internet that force the camera to always select 1/200th of a second shutter speed which is a more viable option for casual shooting, but that requires disassembly of some parts of the camera. If you love your trip, 1/200 would be a more practical way to keep shooting it as 1/40th of a second is very slow and prone to motion blur. However, you would need a fast film (high ISO) if you want to shoot low light.

If you still decide it to shoot without modification at 1/40th, it is advisable to use a film with low ISO and good margin for over- or underexposure (high exposure latitude). Kodak Portra 160 or the legendary Kodak Gold 200 would be a great choice. This would allow you to overexpose significantly while still producing a somewhat pleasing image since color-negative film is very tolerant when it comes to overexposure.

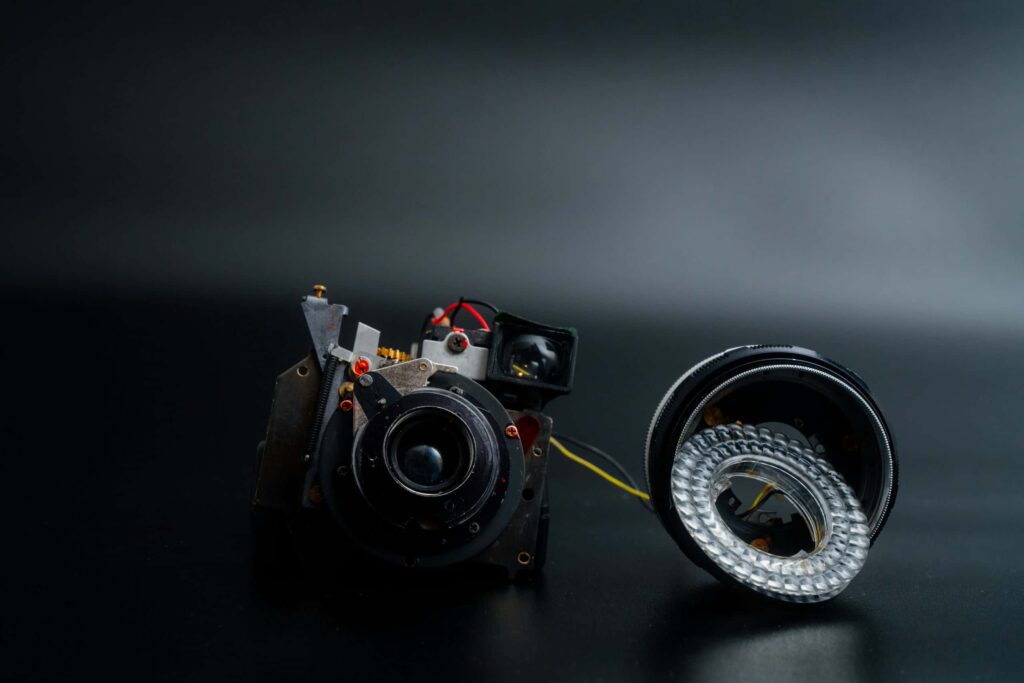

Dissection – How to tell if a Trip 35 light meter is functional?

The only reliable way to tell whether the light meter is working or not is to disassemble the top of the camera and observe the needle. Fortunately, this is a very simple task:

There are merely three screws that need to be taken out, and the top pops right off the body, exposing the light meter.

Once the top is off, you can simply watch the needle: if light shines on the selenium cell, the needle should move. If the needle is moving, the light meter will be functional both in the automatic (A) mode and the manual Flash mode.

You can double-check by observing the aperture blades in the automatic mode:

Point the camera at a bright window and take a picture, looking into the lens. The aperture opening should be fairly small. Now cover the lens with your hand so that the shadow falls on the selenium cell. Take another picture and observe the aperture blades again: they should open up significantly more, demonstrating that the light meter is working fine.

If it does not move it means either the cell is completely dead, disconnected from the meter or degraded enough to produce insufficient voltage to pass the internal resistor.

Ghost in the Machine

Four of the six Olympus Trip 35s I bought for this test were functional. All of them were being sold as defective or for parts. One camera that ended up working straight out of the box stated that the light meter was dead. The seller even asked me if I really wanted to buy a ‘broken’ camera. A moving needle proved the opposite, powering the camera’s automatic features.

It seems that all declared dead Trip 35’s were having minor issues with the raising red flag, making the seller believe that the selenium meter was broken – which it was not. That is because there is much confusing information for sellers who do not specialize in camera gear. They open up the first articles they find and perform these ‘tests’ without actually understanding how the camera operates.

Some red flags were easy fixes (a bit of bending), and some needed more tinkering and disassembly. In the end, four of the dead cameras could be used in the automatic mode. Two of them are working now, including the entire red flag mechanism and the blocked shutter.

The other two expose correctly but do not block you from taking underexposed images. However, this is only an issue in low-light scenarios and can actually be an advantage if you know what you are doing:

The selenium metering is not always precise, especially in difficult lighting scenarios (f.e. bright light in a dark environment), making the camera assume that there is not enough light for a proper exposure while there actually is. The red flag would block you from taking an image in those conditions while the flag-less Trip 35 allows you to press the shutter.

A telltale sign of a truly gone Trip 35 was signs of many attempted repairs or incomplete reassembly. Very loose lens parts, extensively worn-out screws, and peeled-off body covers were all present in the two dead cameras.

It was astonishing to find that the light meter was much more reliable than I thought after researching the camera. I was under the impression that most of the cameras sold were bricks. My (admittedly very anecdotal) experiment proved me wrong.

Should I buy “broken” Trips?

Of course, this does not mean you should go out and buy any Trip 35 listed as broken or condition unknown. However, this might help shed some light on why seemingly broken cameras are mysteriously still producing great images out of nowhere – as if there was a ghost in the camera.This article is simply trying to explain my experience:

I researched this camera intensely, reading repair guides, archived articles, modern blog entries, and of course disassembled and repaired several Trips myself. I can safely claim that I know plenty about photography and cameras and even I had difficulties digging through all the sources and problems associated with this camera. An average seller on eBay neither has the time nor the expertise to figure out all of this. They rely on simple tests or the first articles/videos they find, often performing only rudimentary tests. Since many articles contain wrong or incomplete information, this means there is a good chance that something was missed.

Further Reading

A collection of articles with good information on the Olympus Trip 35

Must read Flickr Thread

The most interesting thread on the Trip 35s automatic exposure features & behaviors:

https://www.flickr.com/groups/28342859@N00/discuss/72157615318255766

Jim Simon Photography’s thoughts on the Trip

Great article about how a working Trip 35 operates and what you can achieve with the flash mode:

http://www.jimsimonphotography.co.uk/olympus-trip-35

Sources

- Figure taken from: https://archive.org/details/20thcdesign0000mcde/page/356/mode/2up?q=%22Olympus+Trip+35%22

- http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Olympus_Trip_35

- Source: https://archive.org/details/newsweek74octnewy/page/n85/mode/2up?q=%22Olympus+Trip+35%22

- Source: https://archive.org/details/dailyuniverse23109asso/page/4/mode/2up

- Sources: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willoughby_Smith , http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Rhamstine

- Source:https://archive.org/details/dailycolonist19721011/page/n53/mode/2up

- Source: Olympus Trip 35 manual found at https://www.cameramanuals.org/olympus_pdf/olympus_trip_35.pdf#page=10

1 Comment